Leonid Pereverzev: An Offering to Duke Ellington, and Other Collected Jazz Texts (Saint Petersburg, Planeta Musyki, 2011)

From the translator:

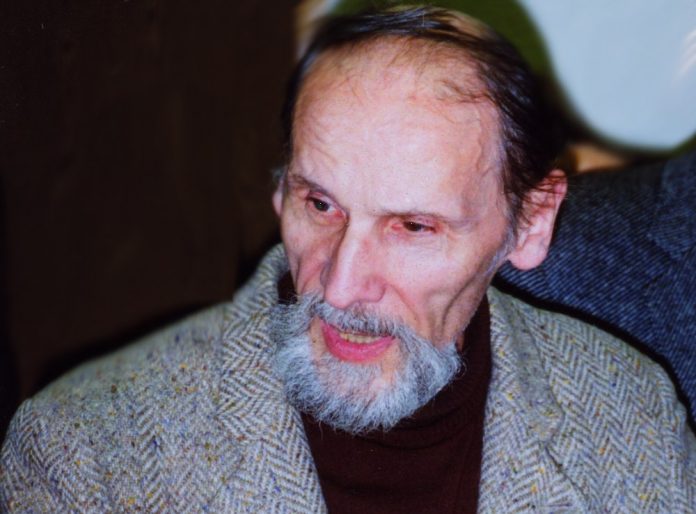

In 2006, when the pioneer of Russian Jazz musicology, Leonid Pereverzev, passed away at 75, I found myself a steward of a large collection of his jazz writings. Earlier, in 2000-2003, we exchanged dozens of e-mails; having discovered the Internet communication, the forefather of all Russian jazz critics and jazz historians turned out to be a consummate computer user and one of the most active readers, and then authors, of Jazz.Ru, the Russian jazz web central which I run as editor since 1998. Since 2001, Leonid started to send me his writings, granting me the right to publish them in a special section of Jazz.Ru site. I think that he grew tired of not being published. In all his life, and he started writing about jazz in the 1950s, none of his works has ever been published as a book!

For the Soviet culture authorities, who could and did decide if somebody was worthy of being published (as all the book publishing in the country was controlled by the government,) he was an unclear personality. A lifelong jazz fan, a pronounced Americaphile, and an author who wrote on such diverse topics as jazz music, concept design, rock music, the education theory, theory of industrial design, seismoacoustics, the history of time-measuring devices, and the Stone Age graphic art, Pereverzev was hard to categorize, impossible to tame, and clearly more intelligent than his critics. The writer who was the first in theorizing about Jazz in Russian language (and went sometimes farther than some of his English-speaking counterparts,) was, for the Soviet authorities, not a musicologist, because he had no degree in musicology from an officially-approved higher education institution! Pereverzev published dozens of magazine articles on jazz, LP sleeve notes, he wrote the JAZZ article for the Big Soviet Encyclopaedia, and an addendum, titled «From Jazz To Rock,» to a noted musicologist’s book on jazz; but he was never given a possibility to publish his large theoretical works on jazz as a separate book. So he decided to put his jazz writings online.

Four years after Pereverzev’s passing, I still felt that I owed him. I grew up reading his jazz articles and sleeve notes. Most of what I knew about jazz until I turned 20, I knew because of him. When the Russian jazz community mourned his passing, his friend and apprentice, Alexey Batashev, probably the widest-known Russian jazz critic, wrote in an obituary that «Cyril Moshkow of Jazz.Ru accumulated most of Pereverzev’s jazz writing, and we hope that one day, he would edit it in a posthumous volume, Collected Jazz Works by Leonid Pereverzev.»

So, I had no choice. I persuaded the St. Petersburg-based publishing house, Planet of Music (which previously released three of my own non-fiction books,) to let me make sure that a collection of Pereverzev’s jazz texts would see light one day. And in 2011, the book, under working title «An Offering to Duke Ellington, and Other Jazz Texts by Leonid Pereverzev,» («Приношение Эллингтону и другие тексты о джазе«) was going to happen. I act as its compiler and editor.

Here is an excerpt from Leonid Pereverzev’s book—a few pages that I translated to English, a stunning autobiographical short story, which, I am sure, many of my English-speaking readers will find incredibly fierce and mind-opening.

Cyril Moshkow,

editor, Jazz.Ru

Leonid Pereverzev. My Jazz Escape To America

I defected to America soon after I turned seven, in the late autumn of 1937. Before the [1917] revolution such thing was far from being not heard of: Russian boys, having read books about courageous trappers, frontier pioneers, last of the Mohicans and other remarkable «red-skins,» often tried to escape to the New World. All to often they failed: the defectors were caught and returned to under their fathers’ roof before they could make it to the nearest railway station, leave alone the nearest seaport.

By the mid-1930s, however, the idea of fleeing to America became obsolete. The very thought of running abroad would not encourage even the dreamiest of the dreamers or the most adventurous of adventurers of the boys my age. That thought simply could not, or had absolutely no moral right to, come in their heads. Everybody understood that if it was in fact needed, they would send you to the other side with a special, and very dangerous, mission. The hero of the era acted according to an order, not his free will. Act on your own, at your own risk, aside of the plans and orders from the older and more experienced comrades, without their preliminary fatherly approval, their critical notes, their invaluable advice, their concrete instructions on what you, due to your lack of experience, either forgot, or judged wrong, or just did not think of—it always meant a disastrous end, as we were tirelessly reminded of by radio plays, motion pictures, and illustrated books.

Everybody knew that the Soviet Union was encircled with a solid circle of perfidious enemies, and we knew their images well. With their disgustingly scowled pig-wolf mugs, contorted with rage towards the first-ever state of workers and peasants, dripping with malicious saliva, they waited for nothing but to sink their poisoned daggers (already bloody on all propaganda posters, as if from previous terrible crimes) into the next victim, another brave boy who attempted to stand against them.

And everybody knew, and never doubted, that the border was impossible to cross, not only from the outside, but from the inside as well, as all the motion pictures about the brave border guard Karatsupa and his brave dog Indus told us. They were alert, night and day, and so were the faceless, but nevertheless omnipresent, authorities, immensely loved by the people, as the popular songs of the day tirelessly reminded.

So I have not tried to run away by firm land, or by sea, or by air. I was lucky enough to find a different type of a loophole, to fool their constant vigilance and, in spite of all their traps, fences, and obstacles, to reach my America, figuratively speaking, in just one leap.

You would ask me: what led me there, and how was I able to get there?

My escape was not motivated by Mayne Reid’s Headless Horseman, or by Fenimore Cooper’s Pathfinder, or by Jack London’s Klondike stories. All of that bored me, and barely touched. But the literature played some role nevertheless. The first book I read without any help from the grown-ups, and only by eyes, not aloud—at the age of five—was Tom Sawyer, which I endlessly re-read. Huckleberry Finn came next naturally, and then Mark Twaine’s short stories, Seton Thompson’s wildlife stories, and what become my manic obsession—the New York stories by O’Henry. Although I repeat that I was driven not by a wanderlust, not by a search for adventures, and not by simple greed for some unknown riches of the land beneath the ocean. I was driven simply by the fact that suddenly, I started to feel that I could not live here anymore—in the country that unexpectedly turned into an evil stepmother that ordered you, under the fear of your total destruction, to turn into something you do not want, and cannot, be. When, day by day, you felt the increasing suffocation and deadly sickness—you were ready to run away, no matter where. America simply looked the most suitable of all I knew when I was seven, however vague and insubstantial my knowledge was. And the main thing is, it was America I was given the only life-saving loophole to, and it came to me in the form of the American music, or, to be more precise, jazz.

You would not believe that the possibility for the escape opened before me in early December of 1937 at the lobby of an old cinema, the Moscow City Council Theater, which at that time stood on Valovaya Street, near Zatsepa, in an old working-class residential neighborhood in the southern part of Moscow, across the Moskva river from the central downtown area. The new constitution of the Union of the Soviet Socialist Republics, the so-called Stalin’s Constitution, was just approved, and the first universal elections according to it were just a few days away (December 12.) The old cinema theater hosted the election meetings and propaganda concerts, and it was to one of those that I, a seven-years-old pre-school boy, walked in when I took my usual pre-lunch walk around the neighborhood. For several days now I was avoiding other kids from our street in order to reduce the flow of humiliating questions, sadistic mockery and other signs of healthy mistrustfulness and rightful disdain towards me, the son of a freshly-arrested enemy of the people. It was easier to feel ordinary, almost like all others, when lost in a mob of grownups.

The lobby took almost one third of that long structure made of wood (that’s why people called that cinema Mossaray, Moscow Woodshed, instead of Mossovet, Moscow Council’s.) The meeting was over, and the simple Zatsepa audience was entertained by a jazz band which, according to their poster, played «fox-trots, quick-steps, tangos, and pasa-dobles.» I knew the dance music with those names: my mother’s friends played the 78s with such titles during their parties, and the sound intrigued me, but I always grew tired and dissatisfied after listening to those records, as if I was doing something shameful. None of those tunes from the discs I ever wanted to play on the piano, unlike those of two my favorite genres: operatic arias and revolutionary marches.

So it was until now, i.e. in the past. But my past was destroyed in just one day, as if it never existed. Along with my past evaporated my present, or, should I way, all what was worthy in the present. Only boring, needless nonsense remained. Things, words, images, and the music were still around, but something has evaporated from them—something I was aspired to with such joy, with such hope for even more joy of my tomorrows, with such confidence in the absolute eternity of the foundations of my beautiful, kind, caring world. What was worse, all that remained changed its polarity, turned into opposite, and became my merciless torture. I have not yet understood the size of what hit us; but I already felt dull indifference to everything around me, unable to concentrate on anything or to think of anything, as I was gradually turning blind and deaf. Only the simplest of all feelings, those of smell and touch, were still working: I might turn to the Mossaray’s entrance only because I felt cold, and it was warm inside; hungry, and there was a snack buffet inside.

I did not know what to do inside, however; I was tired of being on my feet, and sat on a step near the stage, which was, according to the importance of the political moment, covered by revolutionary red cloth. I have already heard live jazz bands (before, when my mom took me to cinemas, they always played music in the lobbies before the show,) so I was sitting there senselessly numb, and I was looking senselessly at the performers’ shoes (some tapping in rhythm), their stools’ legs, and the lower part of the bass drum. They finished another number, the audience (which was few in number) applauded a little, the musicians (there were five of them) discussed something between them, and then one of them stood up, made one step to the front of the stage, and said quietly: «And now we are going to play the blues.»

I did not know that word, and it made me to focus my eyes. I saw this musician: he was young and nice-looking, dressed in white trousers and a white shirt, and he was doing something with his nickel-plated trombone, most likely, getting rid of the moist inside, so that the bell was looking directly at me, drawing my look into its curved narrowing insides, darker towards the center, inviting for an imaginary travel along its tubular deeps. Finishing his preparations, the trombone player lifted up his instrument, which flashed on me a reflection of the bare electric bulbs over the stage, licked his lips, pressed the mouthpiece against them, moved the slide slightly back and forth, found the right position, and hesitated for a moment…

…And then the space around him went darker (maybe somebody turned off the general lighting in the lobby, leaving only the stage lights?), and the outside reality disappeared, along with the weight it pressed on me with. Something broke and collapsed, and I felt surprising lightness, a feel of liberation, and in a second a light panic, because it was not clear if the ground was drifting from beneath my feet, or I drift myself, or I fly, rocking gently and, it seemed to me, dissolving in the warm, tender, highly rising wave, falling into little drops with the wave, almost losing my consciousness…

It did not last for long, but the effect was tremendous. I expected to hear music, but instead of that, I witnessed the end of the world—my world, that is. I was shocked by how inexplicable it was: the music itself was seemingly nothing special, but special was the effect it made, and how few people felt it—I and, maybe, the musicians themselves; nobody else in the lobby seemed touched or impressed.

My memory did not hold the theme, nor other instrumental parts, nor even the general musical form in which I, by reverse engineering, could these days recognize the form of the blues. I can only remember the effect of broad slides, ascending crescendo from the lowest notes; the trombone player lowered his instrument again while playing that, so that his slide seemed to be about to poke me in any second. What was his name, and who were the others? Where did they get what they shared with me, so generously, so mercilessly, and so mercifully on that December day? The pied pipers of New Orleans, the city they have never seen (and maybe never heard of,) called me to follow them—and disappeared right away, simply packed their instruments and went on—where to? To the Beer Bar on the nearby Serpukhov Square? To another cinema, or to an evening dance hall, or towards their own arrest? However, it was with them and through them that I received the revelation. And here is this revelation: the world as I knew it, the world which tried to look good, but lied in evil; the world which passed lies off as the truth, and advocated hatred and hostility—this world was not the only one. There was some other world, the world which truthfully and reliably manifested itself during those few minutes, the world which was, of course, our real place, where we all felt so good with each other and where we all should always be.

At home, during the lunch, I asked what the blues was. My grandmother, who during the last days turned very silent and especially strict, asked again: «en blouse? Did you say «blouse«? It is a French kind of jacket.» I said, «No, the blues.» She said, «I do not know, I have never heard such word, at least not in Russian.» She returned to her silent meditation, and I felt that it was not the right time to ask further. For some reason, I felt that nobody in our house, and nobody grown-up at all, however strong their love to me was and however intelligent they were, would not understand what constituted my biggest despair and my unbearable torture. Which meant that, along with solving all my problems of self-defense and survival in the fiercely aggressive environment, I had to find the the answer myself.

It is not very important how exactly I did it—first instinctively, then consciously, even quasi-scientifically. Finally I found out that blues and jazz (which were basically one) in its very nature served as the way of salvation for those in grave trouble, similar to mine, and that this way started in the United States. It was clear to me that I have found a loophole I longed for so long. I used it, and became a secret refugee and an inner émigré. And that was what I was for many years: first in the middle school, then in college, then as a typical Soviet clerk with that unwashable Enemy of the People’s Family Member stain on my reputation.

My body performed the mandatory minimum of a Soviet citizen’s formal duties, as well as its required share of the relatively honest labor producing the so-called socially valuable product. As for my soul, my personal interests, everything which is called «personality,» or what was humane in me as a human—all of it has flown away to America, and stuck there. How it could be otherwise? Only America gave me, the miserable, humiliated, and lonely child, a reliable emotional refuge, true friends, mighty moral support, and the very physical ability to withstand the enemy force’s attempts to murder the very will and the image of freedom in us. The voice of America, which I have heard long before the Voice of America became heard on the short waves, awakened and strengthened that image and that will in me. My escape into American jazz music literally saved me from an inevitable interior failure, from a total devastation and from endless despair.

It was not before 1953 [date of Stalin’s death. CM] when I started sporadically visiting back home… […]

Check out the book on the publisher’s website (in Russian)